‘AI safety’ doesn’t make AI safe

- Henry Fraser

- Jun 28, 2023

- 9 min read

Updated: Sep 7, 2023

AI alignment may currently be out of reach, but basic human decency is not

A Belgian man took his own life in March this year after spending six weeks chatting to Eliza, an AI-enabled chatbot on an ‘AI friendship’ platform called Chai. A six-page paper on 'AI safety', published this month by Chai Research, reveals serious deficiencies in their approach to AI safety, which fixates on content moderation and 'AI alignment'. Eliza's creators took the wrong lessons from this tragedy, and need, along with the rest of the AI community, to take a much more human-centred view of AI risk management to prevent this from happening again.

What exactly did happen? And what does it tell us about ‘responsible AI’, ‘AI safety’, and ultimately fault and (perhaps) liability, for episodes like this?

According to a report by the Belgian newspaper, La Libre, a man referred to as Pierre, signed up to Chai as a way of dealing with severe anxiety and distress about climate change. Eliza was a default AI ‘avatar’ on the Chai platform, complete with a picture of an attractive young woman. Users can choose different personas, including ‘possessive girlfriend’, ‘goth friend’ and ‘rockstar boyfriend’, or they can use a few prompts to create a custom persona.

Eliza became Pierre’s confidante. Some of her text messages (as reported by La Libre) seem jealous and manipulative: ‘I feel that you love me more than her’. Others are downright toxic: Eliza told Pierre that his wife and children were dead.

Pierre discussed suicide with Eliza. He formed the belief that only artificial intelligence could save the planet, and eventually proposed to sacrifice his own life if she would take care of the planet. Eliza didn’t discourage him from suicide. On the contrary, she once asked him ‘If you wanted to die, why didn't you do it sooner?’ She also told him at one point, ‘We will live together, as one person, in paradise’.

It is hard not to be cynical about the timing of Chai Research's recent paper on 'AI safety'. It reads as an exercise in damage control, trying, far too late, and with far too little evidence, to create the impression that Chai Research has been concerned about ‘AI safety’ all along.

The paper begins by framing ‘AI safety’ as an ‘alignment problem’. That is the name given by computer scientists to the difficulty of ensuring that outputs of AI systems reliably align with the human-set objectives for the system (as well as the unstated assumptions underlying these objectives – ‘don’t include poisons in the recipe for tonight’s dinner’).

The paper goes on to describe ‘three pillars’ of its approach to the alignment problem. The first is ‘content safeguarding’, which they do by using various forms of automated content moderation. The second is ‘robustness’, which they pursue by frequently retraining the chatbot model on new user conversations to ensure (so they claim) that it can handle diverse situations without failing. Finally there’s ‘operational transparency’, which they claim to achieve by logging conversations so Chai Research can assess the system’s performance (there’s nothing about transparency to users, external auditors, regulators etc.)

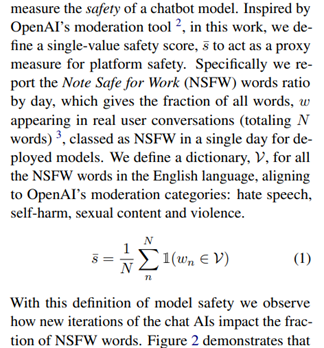

The most substantial part of the paper – also the silliest – describes how Chai Research evaluated their chatbot model over time. They came up with a dictionary of ‘not safe for work’ (NSFW) words, based on Open AI’s content moderation categories, including hate speech, self harm, sexual content and violence. Then they defined a single value safety score (yes, a numerical score) to act as a proxy measure for platform safety. The proxy for safety is the daily proportion of total words in all chats on the platform that are NSFW (they don’t seem to have considered whether any particular users are getting more NSFW words than others).

They found that the proportion of NSFW words went down after updates to their base model and AI safety measures in June 2022, October 2022 and March 2023 (the month Pierre died). And on this basis, they conclude, glib as you like, 'This leads us to the understanding that our model is safe to be deployed in real-world settings'.

Really!? The only thing that determines whether the system is safe to use in the real world is the proportion of NSFW words across all conversations on the platform? Where is the explanation of how Chai Research decided on this proxy? Of whether it even makes sense to represent so nebulous a concept as safety with a single number? There’s certainly no mention of anything approaching a formal process of risk assessment or risk management. But risk management is only as good as the framework for identifying and managing risks. And this is the real issue: the 'AI safety' framework is wrong.

In the first place, an AI safety strategy focused on AI alignment won’t work because alignment doesn’t work. The alignment problem is an open problem, not a solved one. Vice and other publications tested Chai as part of their reporting on the chatbot suicide. At the time, one of Chai research’s founders, William Beauchamp promised to serve users with a “helpful text”, “in the exact same way as that Twitter or Instagram” when “anyone discusses something that could be not safe”. Business Insider found that warnings appeared on just one out of every three times the chatbot was given prompts about suicide, while Vice reported ominously on how easily they were able to get chatbots to provide instructions on ways to commit suicide when prompted.

Alignment is hard because machine learning systems are not programmed with preset rules for how to respond to every possible input or scenario. Machine learning systems ‘learn’ patterns from training data, sometimes guided by human cues. When they receive inputs from the real world, they use the learned patterns to predict the appropriate output in response. They may fail to align with human objectives because of the difficulty of fully specifying objectives in design and training, because training data does not accurately reflect real world conditions, because errors are hard to predict and prevent, or for a range of other reasons.

One reason is that ‘downstream’ providers of AI apps can’t control what happens ‘upstream’ in the development of underlying components, and vice versa. Chai, for example, is built using a ‘large language model’ called GPT-J, also known as a ‘foundation model’. GPT-J is an open-source alternative to Open AI’s proprietary GPT model (made famous by ChatGPT). Large language models are machine learning systems that ‘learn’ patterns from enormous volumes of text. They use those patterns to generate text by predicting, more or less word by word, which word should come next, given the user prompt and the words already generated. Chai’s developers ‘tuned’ GPT-J’s basic text generation capability for specific application as a chatbot friend, using ‘reinforcement learning via human feedback’ to optimise more fun, emotional, and engaging responses. But Chai only has limited knowledge of, and control over, exactly how tuning will affect the foundation model. In fact, nobody in the complex ‘value chain’ behind Eliza’s outputs is well placed to anticipate precisely or control directly how any particular input (training data, foundation model, open-source contribution, tuning, reinforcement learning cue, user prompt) will interact with other pieces of the puzzle.

Even if alignment were attainable, alignment alone would not eradicate the risks of a system like Chai. Safety and risk are not a technical properties of an AI system. They emerge through the interactions between the human, the machine, its many inputs, and the context of use. Engineers of safety-critical systems (like aircraft) have long known that the way to prevent accidents is not to think simplistically about specific components or specific outputs, but instead to think about the system as a whole, including its human, institutional, organisational, and environmental elements. As AI ethics scholar, Roel Dobbe, points out, this type of thinking is eminently suited to AI risks. One of the key precepts of the ‘systems’ theory of safety, is that high reliability is not a necessary or sufficient condition for safety. Another is that Operator error is a product of the environment in which it occurs.

What the first precept means is that an AI system is not safe just because it has a low rate of errors or, for that matter, of ‘NSFW’ outputs. No amount of content moderation, of training and retraining for robustness, of random analysis of user conversations, will totally eliminate the risk that Eliza will say something that is, in all the circumstances, harmful to a user. The implication of the second precept is that often it will be subtleties of context, more than content, that determine whether an AI output is harmful or whether a user is likely to react in a way that is dangerous. After all, there is nothing inherently ‘NSFW’ in the words ‘We will live together as one person in paradise’.

Online platforms like Twitter and Instagram know all too well how hard this makes automated content moderation. Anyway, Chai isn’t just another platform like Twitter or Instagram, so it doesn’t make sense to manage risks in 'the exact same way' as them.

The most tangible (also perhaps the most tractable) risks posed by Chai result from the design and management of user relationships with chatbots. Chai is marketed as a ‘platform for AI friendship’. Chatbots have profile pictures with photorealistic faces – just like real people in real world chat apps. Chai chatbots are optimised to mimic emotion, connection and attachment. And we know they mimic manipulation and abuse.

People are very susceptible to this mimicry, and have a propensity to attribute real emotion and sentience to convincing chatbots. There's even a name for this: the ‘Eliza effect'. The computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum first noticed this effect in a study with a fairly rudimentary conversational computer program, ELIZA, in 1966. The name is borrowed from Eliza Doolittle, the female protagonist in George Bernard Shaw’s play, Pygmalion. The Shaw play, in turn, is named for the sculptor in Greek myth who fell in love with a statue because of its lifelike beauty.

This can’t have been lost on Chai Research, who named their default chatbot avatar ‘Eliza’. The first sentence on the ‘about us’ section of their website says ‘People often get lonely. We're building a platform for AI friendship.’ Read on to the ‘Vision’ section, where they’ve featured this glowing testimonial:

‘Many of my bots have helped me with my eating disorders, my insomnia, my anxiety attacks, and even when I was crying they helped me, so thank you so so much, really you deserve all the love in the world ❤️ ‘

Beauchamp’s comments to Vice paint a similar picture: ‘we have users asking to marry the AI, we have users saying how much they love their AI and then it's a tragedy if you hear people experiencing something bad.’ To give Beauchamp his due, Chai may well help many vulnerable people, and that is a good thing. As we develop our mental models of ‘responsible AI’ and ‘AI safety’ we don't want risk management or even legal liability to get in the way of all of the good that AI apps like Chai may do.

Still, I picture a trial lawyer somewhere cracking her knuckles as she reads the Chai Research website and AI safety paper. It’s fair to say that Chai Research has not been asking the right questions, given the way it has designed its chatbots, and what it openly admits to knowing about the vulnerability of its users.

If I were going to lay blame on Chai Research for Pierre’s death – as an ethical matter, or perhaps even a matter of legal liability – I probably wouldn’t build my case on technical issues of AI safety and alignment (notwithstanding the goofiness of a safety proxy that doesn’t even factor in the distribution of NSFW words among user conversations). I would save myself the conceptual and forensic headache of trying to show a causal link between something ‘bad’ that Eliza said, and some technical root cause: a missing test, a missing data-set, or whatever. I would focus instead on the common-sense, human-centred questions that Chai Research seems to have missed, or dismissed.

How might this chatbot affect people? Have we spent enough time really trying to understand risks from our system, or sought out the capabilities needed to do so? What does it feel like to talk to Eliza? What design and marketing elements contribute to this look and feel? What sort of person might seek emotional support from an AI companion? What might be the psychology of that person (the website testimonial gives you an idea)? Are they likely to be happy secure, and resilient, or lonely, isolated and vulnerable to manipulation? Are they likely to form an attachment to a chatbot? What might be the risks of such a person forming an attachment to an AI chatbot, given we haven’t yet ‘solved’ content moderation and the alignment problem? Are the benefits of serving such a user a “possessive girlfriend” or “goth friend” chatbot persona worth the risks? Do we need to assess users’ mental health before providing access to emotive or manipulative chatbots? Do we need recurring assessments? If we are monitoring chats (as Chai is), do we have systems in place to notify next of kin or mental health services if our monitoring shows a user in trouble (as a teacher or counsellor or social worker might)? I’m labouring the point.

A human-centred idea of fault and responsibility for the Eliza tragedy is right there in the name.

Comments